The Farthest Horizon

A Guide to the Short Fiction of Raymond F. Jones

Raymond

F. Jones was a fan of science fiction stories in his teens and early twenties, an avid

reader of pulp magazines such as Hugo Gernsback's Amazing Stories. Like many

others, his enthusiasm for the genre prompted him to try his hand at writing his own

stories, with a view to eventually being published himself. His first published story was

"Test of the Gods" for the September 1941 issue of Astounding

Science Fiction. The vast majority of his work in the most prolific period of his

career (roughly 1941-1957) appeared in the pages of Astounding Science

Fiction magazine whose editor John W. Campbell encouraged his contributors to write

scientifically credible "problem" stories. It is his work in this sub-genre that

gained Jones the most reknown but it should be noted that he did write well, and often, a

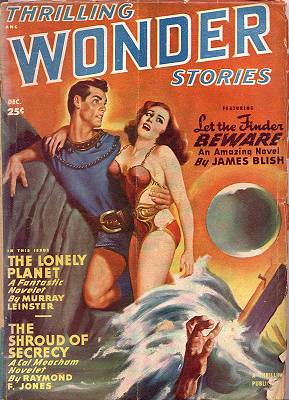

number of very different stories for magazines such as Planet Stories and Startling

Stories.

Raymond

F. Jones was a fan of science fiction stories in his teens and early twenties, an avid

reader of pulp magazines such as Hugo Gernsback's Amazing Stories. Like many

others, his enthusiasm for the genre prompted him to try his hand at writing his own

stories, with a view to eventually being published himself. His first published story was

"Test of the Gods" for the September 1941 issue of Astounding

Science Fiction. The vast majority of his work in the most prolific period of his

career (roughly 1941-1957) appeared in the pages of Astounding Science

Fiction magazine whose editor John W. Campbell encouraged his contributors to write

scientifically credible "problem" stories. It is his work in this sub-genre that

gained Jones the most reknown but it should be noted that he did write well, and often, a

number of very different stories for magazines such as Planet Stories and Startling

Stories.

His obvious technical knowledge, gained from careers as a radio engineer and government meteorologist, shines through in his writing. He did however manage to balance his stories by presenting his ideas and speculations in an accessible manner; his work background would often merely serve to give his tales an authentic taste. One example that shows how his career experiences influenced his work is the story "Forecast" (1946). This is a tale of the employees of a near future "weather control" station, a plot idea that was clearly inspired at least in part by his time with the U.S Weather Bureau. The engaging plots that typified his output during this exciting period may have intentionally served as vehicles for enabling the reader to more readily assimilate forward-thinking ideas in the fields of physics and psychology. In his most purely "Campbellian" stories, there was often a soundly conceived and convincing conclusion orated by the protagonist at the end of the story. The cogency of these summings up did not, however, fully hide the influence of Campbell, whose own opinions were expressed in his lucid and provocative editorials. Transcripts of letters between Jones and Campbell do show that their working relationship was instructive for both parties and that there was a healthy exchange of ideas between them. It can only be speculated upon today how much one influenced the other.

What set Jones apart from the crop of regular Astounding contributors was his singularity of voice, his sharp dialogue, his ability to draw believable characters and the passion with which he held his subject matter. Jones had a talent for the impartation of stories that exhibited lengthy processes of logic, reason and a clear analytical approach to moral dilemmas. Interestingly, he often had a quite sobering point to put across in his plots. One recurring theme is that mankind may not be morally developed enough to be trusted to handle new inventions and potentially dangerous scientific breakthroughs. This theme is explored to great effect in "The Person From Porlock" (1947).

Jones' characters were invariably called upon by alien beings to decide whether to continue striving for short term goals which, however attractive, may endanger the long term welfare of the human race. Nevertheless, the majority of his stories championed the need for scientific freedom and the liberation of developmental research. More often than not, Jones expounded the view that the potential of the human mind has only just been tapped and furthermore, that revolutionary techniques in the interpretation of electroencelographic studies be harnessed and used more effectively. The breaking down of mental borders, dealt with in stories like "The Great Gray Plague" (1962), is a common theme for his plots, though in his later writing Jones explored entirely different themes.

Typical stories that merit special attention include: "I Tell You Three Times" (1951), about the influence of decision-making computers on politics and morality; "Intermission Time" (1953), a social experiment on an alien planet; "Noise Level" (1952), a much cherished story of a group of scientists and their endeavours to invent anti-gravity - a story that embodied the whole ethos of Astounding Stories in the 1950's; "The School" (1954), and it's sequel "The Great Gray Plague" (1962), the development of the mind; "Academy for Pioneers" (1956), a test of a man's moral strength to assess his suitability for inclusion in a space colonisation program; "Cubs of the Wolf" (1955), one of his best stories, an endearing tale of human/alien diplomacy; "Doomsday's Color Press" (1952), an accomplished novelette with an involving semantic argument about the psychological power and influence of the printed word; and "The Non-Statistical Man" (1956), a detailed, labyrinthine tale championing mankind's latent intuitive capabilities and social change.

Moreover, one cannot stress enough that Jones in the 1940's to 1950's period was not just a "hard sf" writer. Much of his short story output was space opera with his own idiosyncratic style obvious throughout. Very early works like "Pacer" (1943), were typical scientific problem stories but with an adventurous tone. Other exceptions were: "The Wrong Side of Paradise" (1951), an alternate dimension fantasy; "Canterbury April" (1952), a paradox/time travel story, a subject he dealt with more than once; and "The Farthest Horizon" (1952), a sensitive tale of a family's dilemma of priorities in the early days of space exploration.

Raymond F. Jones' son, Richard, remarked that his father lived with his wife and family in Phoenix, Arizona from the mid 1940's to about 1952. During this time Raymond F. Jones converted a cinder block building in his back yard (which he had originally built to house chicken coops) into an office. It was from here that Jones wrote all his stories from roughly 1947 to 1952, before returing to live in Utah. This was a very important period for Jones as it was during this time that he really found his feet in the sf magazine world and decided to make a go of it as a full-time writer. There followed throughout the 1950's some of the finest stories Jones ever wrote. Among these were "A Matter of Culture" (1956), a startling tale of one man's attempts to understand a seemingly incomprehensbile alien culture and "The Strad Effect" (1958), a playful and witty take on one of Jones' favourite themes - the hidden capabilities of the mind.

After 1957, Jones' stories became much less frequent. He reverted back to writing science fiction on a part-time basis at some point in the mid 1950's, taking up a job as a technical writer for Sperry, Utah and staying there until his retirement. It is almost certain that work commitments prevented him from contributing to the field more than occasionally. Jones is also said to have had a keen interest in photography and model railroading, hobbies that no doubt occupied much of his time. However, Roger Elwood (who was to publish virtually all of his work in the 1970's) has stated that Raymond F. Jones felt there was a general lessening of quality in the science fiction field as a whole. This may have been a causative factor for Jones' rather sporadic output in the final two decades of his published career. The handful of stories that appeared mostly in Amazing Stories magazine in the 1960's were all impressive. There is much humour and wit in the sparkling "Rider in the Sky" (1964); the suspenseful "Subway to the Stars" (1968), essentially reworks an old theme but with no lessening of vitality and inspirational drive; and "Stay Off the Moon!" (1962), full of foreboding for mankind's scientific activities on the luna surface, has a wry twist at the end showing a darkly humorous side to Jones' work. In addition, Jones' unusual short story "Rat Race" (1966), was nominated for a Hugo award in the Best Short Story category.

All but two of the short stories by Jones that appeared in the 1970's were published in a series of anthologies edited by Roger Elwood. These books were largely geared towards the younger science fiction reader. Elwood encouraged Jones to write, and with renewed vigour that also produced several commendable novels, Jones contributed a handful of whimsical, heartfelt and adventurous tales. The stories Jones wrote in this period had a variety of themes, much different to his earlier work and often had ambiguous conclusions, bordering on pessimistic. However, one cannot deny the beauty of these simply written and entertaining tales. Of note is the story "Reflection of a Star" (1974), a haunting gem about a child's encounter with an alien in another dimension. A particular favourite of mine is "A Bowl of Biskies Makes a Growing Boy" (1973), about a young boy's struggle for personal freedom in a stifling, government-controlled state in which the emotional development of children is hindered purposefully by a food additive that acts upon the growing brain. The young hero of the story discovers this - spoiler follows! - and is then sent with other juvenile "offenders" to a special school where they are gently but firmly steered back into a regressive state of mind.

His last published story was "Death Eternal" (1978), containing reflections on religious faith (a theme that crops up in several of his later stories) and yet another sombre outcome. One feels that Raymond F. Jones was writing exactly what he wanted during this twilight period of his career. It is noted by Raymond F. Jones' son, Richard Jones, that his father gave up writing sf because during the late 1970's he found it hard to find a market for his unique brand of science fiction. His powerful imagination was still apparent right up to the very end but his style simply fell out of favour with the editors of the few surviving sf digest magazines such as Analog, The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction and Galaxy. It's intriguing to note that one story, "The Day of the Puritan," written near the end of his career as a science fiction writer, was rejected by the sf magazines and therefore never published. After giving up writing, Jones followed other pursuits, such as his new role of being a grandfather, until he passed away in 1994 at the age of 79.

It can only be speculated upon which direction his writing may have taken after 1978 and it is a shame that he did not continue. But four decades of solidly written, thought provoking, ingenious and marvellously entertaining stories testify to his fantastic ability in the science fiction field. Perhaps one day an enlightened publisher will reprint in book form his uncollected short stories! The work of Jones has been neglected for a long time now and I hope that this essay goes some way towards redressing the balance.

Richard Simms, 1999.

Revised in 2003.

Raymond F. Jones (1915-1994)

Please check out the Meet the Author page for a special treat - an autobiographical piece written by Jones which appeared in the August 1951 issue of Amazing Stories, as well as a smaller autobiographical sketch Jones wrote for the Summer 1947 issue of Planet Stories.